Note: This is a continuation from my previous post.

One of the key ideas of goputer is frontends. This is also one of it's footfalls. Even though each frontend is written by myself their appearance, foundations, and the way they communicate with goputer (the runtime) itself varies wildly between them. These different implementations have created several flaws, the main one being some subtle differences in visual output between them.

Not only does the user interface vary (which isn't a problem exactly) but so does the the rendered visual output. This means on each frontend the rendered graphics produced by any program looks different. Some use anti-aliasing, some do not, they all use different fonts. The "graphics memory" is also not accessible to a running program, which means in order to change a specific pixel you have to use the vp (video pixel) interrupt instead of just writing to a corresponding memory address.

In order to fix this variation I decided to create a 2D software renderer as a part of the runtime itself. While I could have used a preexisting Go library such as Michael Fogleman's gg to achieve this instead, I only needed a small set of procedures (to draw primitives) plus another to draw an image format, the internals of which I hadn't quite decided upon yet.

#Deciding on the framebuffer attributes

Before the decision to move to software rendering the framebuffer had had a resolution of 640x480 and been composed of RGB8 colours. This is mostly because it seemed like a sensible size (for the retro feeling it was trying to emulate) and sticking with a "normal" colour depth meant that no head scratching was required when it came to figuring out palettes and their associated colours in code.

When switching to software rendering, some compromises had to be made in order to fit it into a sensibly sized piece of memory. The existing memory size was $2^{16}$ or rather 65,536 bytes. This was no where near big enough to contain a sensible video resolution and program data (the largest 4:3 ratio that would fit would be 160x120 which would work out to take 57,600 bytes).

Rather than increase the memory size by powers of 2 until it fit I settled upon taking a resolution of 320x240, then just adding the "program space" 65kb onto the end.

#Drawing primitives

The most simple primitive to draw is a pixel. However, this is only because now no Go code needs to be written for this, just some basic (albeit more code in comparison to before) assembly:

#def pixel_start 4500

#def full_red 0xFF0000FF

#label start

lda @pixel_start

mov d0 r00

lda @full_red

incr r02

sub dl r02

mov a0 r01

// <address> <length>

sta r00 r01

Some more explanation for the code above:

- Define a value for the address of the pixel and it's resulting colour value.

- Load the address value and then move it's result into the register

r00. - Load the colour, and then calculate the correct data size (3 bytes, RGB).

- Store 3 bytes from the data buffer (

d0where the result ofldawas stored earlier) at the address 4500.

Would this be simpler to do with an interrupt like it was before? Yes. Is there any point to doing it now the video memory is part of the main memory? No.

With that out of the way it was time to move onto some actual shapes.

Squares

Squares are arguably the easiest shape to draw (apart from perhaps perfectly horizontal/vertical lines). You just set one line in memory and then if it isn't transparent just copy that region over and over. If the colour happens to be transparent then you have to go and set each pixel one by one. The framebuffer in goputer is actually RGB8 instead of RGBA8, which means the transparency is not true so to speak but that's besides the point.

Lines

Drawing lines required the use of a line drawing algorithm. For this I chose Bresenham's algorithm. The pseudocode was already on Wikipedia so all I had to do was convert it to usable Go code, making use of the relatively new iterator functionality released in version 1.23.

func Bresenham(a [2]int, b [2]int) iter.Seq[[2]int] {

var x int = int(a[0])

var y int = int(a[1])

var dx int = int(math.Abs(float64(b[0] - a[0])))

var dy int = -int(math.Abs(float64(b[1] - a[1])))

var err int = dx + dy

var sx int = 1

if a[0] >= b[0] {

sx = -1

}

var sy int = 1

if a[1] >= b[1] {

sy = -1

}

return func(yield func([2]int) bool) {

for {

if !yield([2]int{x, y}) {

return

}

if x == b[0] && y == b[1] {

break

}

var e2 int = 2 * err

if e2 >= dy {

if x == b[0] {

break

}

err += dy

x += sx

}

if e2 <= dx {

if y == b[1] {

break

}

err += dx

y += sy

}

}

}

}

This iterator function could then be used by other methods which required a line, i.e. polygons.

Polygons

Despite arguably being the most difficult shape to draw, because I had already implemented Bresenham's as an iterator it turned out to be quite easy. I followed the approach detailed in this set of lecture notes, which can be explained in sum as follows:

- Generate the points for the polygon.

- While generating, bucket them (

map[int][]int), with the Y coordinate for the point being the key, with an array of corresponding X coordinates being the value. - Fill in toggling filling based on whenever we cross a line, for doing horizontal lines, check the previous X coordinate as well.

The storage format for the polygon data was simple as well. One byte to denote the number of points, then n pairs of X and Y byte values to represent:

// s x y x y x y

#def poly_data 0x03000080004040

Above is the data for an upside down triangle with 3 vertices: (0,0), (128, 0), and (64, 64). Bear in mind these are relative to what the values of vx0 and vy0 are when the triangle is rendered. The first point doesn't have to be the origin.

I also repurposed the now redundant vp (video pixel) interrupt as the video polygon interrupt instead, with the data being taken from the data buffer.

Text

In order to display text I first needed my own font. While I could have used one that was preexisting (i.e. any pixel font available under the open font license) I only needed a certain set of characters, printable ASCII + an unknown character symbol. Now armed with a slightly ugly font, I just had to write some code to draw a bitmap (font image was exported from GIMP then loaded into an array at runtime) and that was it.

Drawing images

The only functionality I wanted to add which wasn't drawing primitives was the ability to draw bitmaps (glyphs are bitmaps as well however they aren't as fancy as images). To do this I made a very simple image format:

- 4 bytes for the with and height (2 u16)

- 1 byte for flags

- Rest of the bytes would contain the image data

The flags would indicate wether or not the image was compressed (RLE) or had an opaque background. In order to render an image, you have to load the image data (lda) and then move the address value in dp to the data buffer before calling the vi (video image) interrupt. This way of passing information to interrupts may change in the future because it isn't entirely consistent between different interrupts.

Images can be included in the binaries using the following code:

#def image file:"image_data.bin"

Putting it all together

Now I was drawing shapes to the framebuffer I needed some way to see it. To be honest I'd already done this for one frontend however this post would've flowed as well if I had done it the other way round. The first frontend I converted to use with the software renderer was the gp32 (the original, written in Go) frontend.

As I was using raylib I could use it's update texture method. Another option would've been to use an rlgl method, however the one required wasn't exposed in the Go library. Because of this I also had to create a secondary buffer used by the frontend only, as raylib-go required the data to be []color.RGBA and not []color.RGB. This requirement for RGBA meant I couldn't use any unsafe.Pointer magic either as the framebuffer contains RGB values.

These restrictions meant I had to write a conversion loop before updating the texture:

// Update video texture

for i := 0; i < int(vm.VideoBufferSize); i += 3 {

VideoIntermediate[i/3] = color.RGBA{

gp32.MemArray[i],

gp32.MemArray[i+1],

gp32.MemArray[i+2],

255,

}

}

rl.UpdateTexture(

VideoRenderTexture.Texture,

VideoIntermediate[:],

)

However, the web frontend was more complicated. I had two options, a) the ctx.putImageData method, or b) use WebGL and update a texture. Because it looked like the ctx.putImageData method was going to be much slower in comparison, I settled on using WebGL. This also had the small downside of having to make this work despite having virtually zero graphics programming (OpenGL, Vulkan etc.) knowledge.

In order to fill this deficit I started the MDN WebGL tutorial, getting to the part where textures started coming into play before abandoning it and making it work for my use case based on what code I had written so far.

Eventually I got something working and somehow it turned out faster than the Go one. When running in Firefox, each WASM cycle when running the test file had a ~16ms mean cycle time, Chrome had a ~4ms mean cycle time, and the native Go version had a cycle time of ~5ms. This is something that will likely require further investigation, my current suspicions lie with the conversion loop mentioned earlier and not being able to update the texture directly. This might be able to solved by switching to a different graphics library for Go (which will probably be necessary because I want to write a profiler/debugger at some point) but we'll see.

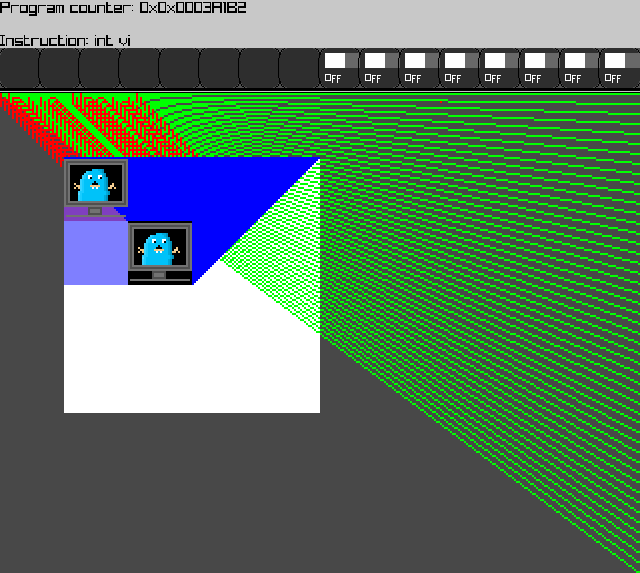

Above is the graphics test file running in the gp32 frontend. The code for that test file can be found here. It doesn't work in the web frontend at the moment because there is no way to import binary files (no access to a real file system) however in the future I plan to use the file system API to fix this.

#Conclusion

In conclusion this proved to be quite a nice sub-project to do after writing mainly Python during my first year of university. It also removed one of the weird quirks of goputer meaning that writing a frontend should be a bit easier now, however audio (generation & output) is still handled individually. Ideally generation, that is the production of sample data based on the corresponding frequency and wave type, should be handled by the runtime as it is platform independent. Frontends will still have to handle input though.

The next major architectural changes will likely be the introduction of a profiler/debugger (making use of a slightly less hobbled frontend) and removing dependencies on Go's plugin package because it isn't cross platform. In the meantime however I'll probably work on something smaller just to take a break.

0 Comments